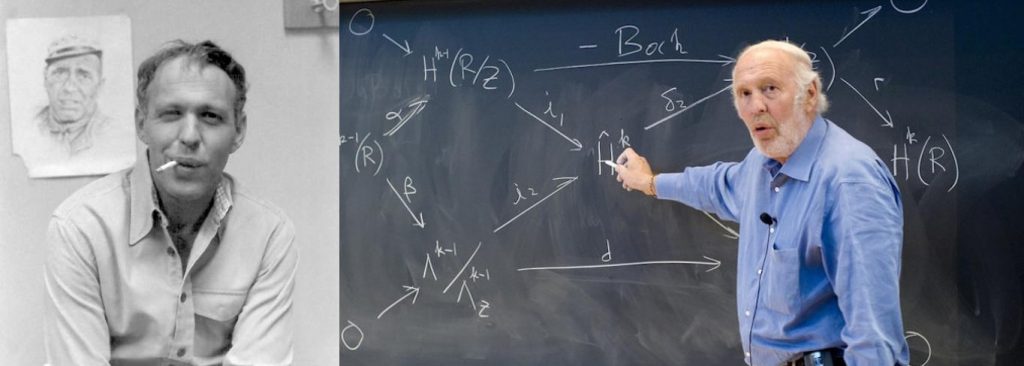

By Gregory Zuckerman, Aug/2019 (352p.)

Excellent book. Well researched and well told, with some great stories and insights into one of the world’s greatest mathematicians and investors. Given how secretive Renaissance is known to be, it is remarkable how much detail Gregory Zuckerman was able to gather and share in an interesting, unbiased way. I was impressed by the inquisitive culture that Jim Simons instilled, and also how the company grew and the culture evolved. It was not an easy path. For example, it was a big challenge for the partners to cope with the wealth that they amassed. Below are two of my favorite highlights on this topic, but there are many other stories and anecdotes:

Some employees seemed embarrassed by their swelling wealth. As a group of researchers chatted in the lunchroom in 1997, one asked if any of his colleagues flew first-class. The table turned silent. Not a single one did, it seemed. Finally, an embarrassed mathematician spoke up. “I do,” he admitted, feeling the need to offer an explanation. “My wife insists on it.”

Peter Brown had mixed feelings about his own accumulating riches. He had long battled anxieties about money, colleagues said, so he relished the big bucks. But Brown tried to shield his children from the magnitude of his wealth, driving a Prius and sometimes wearing clothing with holes. His wife, who had taken a job as a scientist at a foundation dedicated to reducing the threat from nuclear weapons, rarely spent money on herself. Still, it became hard to mask the money. Colleagues shared a story that once, when the Brown family visited Bob Mercer’s mansion, Brown’s son, then in grade school, got a look at the scale of the Mercer home and turned to his father, a look of confusion on his face. “Dad, don’t you and Bob do the same thing?”

Below I share some other passages that I highlighted on our shared-Kindle, in the order they came up in the book.

Conclusion: It’s a must-read.

Best,

Adriano

Highlighted Passages:

HIGHLIGHTS:

“I don’t want to have to worry about the market every minute. I want models that will make money while I sleep.” – Jim Simons

One day Axcom made more than $1 million, a first for the firm. Simons rewarded the team with champagne. The one-day gains became so frequent that the drinking got a bit out of hand; Simons had to send word that champagne should be handed out only if returns rose 3 percent in a day, a shift that did little to dampen the team’s giddiness.

Simons had discarded a thriving academic career to do something special in the investing world. But, after a full decade in the business, he was managing barely more than $45 million, a mere quarter the assets of Shaw’s firm.

Driving to Stony Brook with a friend and Medallion investor, Simons could hardly contain his excitement. “Our system is a living thing; it’s always modifying,” he said. “We really should be able to grow it.

The fund began trading more frequently. Having first sent orders to a team of traders five times a day, it eventually increased to sixteen times a day, reducing the impact on prices by focusing on the periods when there was the most volume. Medallion’s traders still had to pick up the phone to transact, but the fund was on its way toward faster trading.

“What you’re really modeling is human behavior,” explains Penavic, the researcher. “Humans are most predictable in times of high stress—they act instinctively and panic. Our entire premise was that human actors will react the way humans did in the past . . . we learned to take advantage.”

It began the very moment Thomas showed Robert the magnetic drum and punch cards of an IBM 650, one of the earliest mass-produced computers. After Thomas explained the computer’s inner workings to his son, the ten-year-old began creating his own programs, filling up an oversize notebook. Bob carried that notebook around for years before he ever had access to an actual computer.

“Any time you hear financial experts talking about how the market went up because of such and such—remember it’s all nonsense,” Peter Brown later would say.

A classic industry joke: Extroverted mathematicians are the ones who stare at your shoes during a conversation, not their own.

Simons began sharing equity, handing a 10 percent stake in the firm to Laufer and, later, giving sizable slices to Brown, Mercer, and Mark Silber, who now was the firm’s chief financial officer, and others, steps that reduced Simons’s ownership to just over 50 percent. Other top-performing employees could buy shares, which represented equity in the firm. Staffers also could invest in Medallion, perhaps the biggest perk of them all.

Some employees seemed embarrassed by their swelling wealth. As a group of researchers chatted in the lunchroom in 1997, one asked if any of his colleagues flew first-class. The table turned silent. Not a single one did, it seemed. Finally, an embarrassed mathematician spoke up. “I do,” he admitted, feeling the need to offer an explanation. “My wife insists on it.”

“If there were signals that made a lot of sense that were very strong, they would have long-ago been traded out,” Brown explained. “There are signals that you can’t understand, but they’re there, and they can be relatively strong.”

By the fall of 2000, word of Medallion’s success was starting to leak out. That year, Medallion soared 99 percent, even after it charged clients 20 percent of their gains and 5 percent of the money invested with Simons.

“There’s no data like more data,” Mercer told a colleague, an expression that became the firm’s hokey mantra.

Brown had mixed feelings about his own accumulating riches. He had long battled anxieties about money, colleagues said, so he relished the big bucks. But Brown tried to shield his children from the magnitude of his wealth, driving a Prius and sometimes wearing clothing with holes. His wife, who had taken a job as a scientist at a foundation dedicated to reducing the threat from nuclear weapons, rarely spent money on herself. Still, it became hard to mask the money. Colleagues shared a story that once, when the Brown family visited Mercer’s mansion, Brown’s son, then in grade school, got a look at the scale of the Mercer home and turned to his father, a look of confusion on his face. “Dad, don’t you and Bob do the same thing?”

Some of Mercer’s comments were downright abhorrent. Once, Magerman recalls, Mercer tried to quantify how much money the government spent on African Americans in criminal prosecution, schooling, welfare payments, and more, and whether the money could be used, instead, to encourage a return to Africa. (Mercer later denied making the comment.)

In 2002, Simons increased Medallion’s investor fees to 36 percent of each year’s profits, raising hackles among some clients. A bit later, the firm boosted the fees to 44 percent. Then, in early 2003, Simons began kicking all his investors out of the fund. Simons had worried that performance would ebb if Medallion grew too big, and he preferred that he and his employees kept all the gains.

Before they knew it, Simons was lighting up. Soon, fumes were choking the room. The Robert Wood Johnson representatives—still dedicated to building a culture of health—were stunned. Simons didn’t seem to notice or care. After some awkward chitchat, he looked to put out his cigarette, now down to a burning butt, but he couldn’t locate an ashtray. Now the RIEF staffers were sweating—Simons was known to ash pretty much anywhere he pleased in the office, even on the desks of underlings and in their coffee mugs. Simons was in Renaissance’s swankiest conference room, though, and he couldn’t find an appropriate receptacle. Finally, Simons spotted the frosted cake. He stood up, reached across the table, and buried his cigarette deep in the icing. As the cake sizzled, Simons walked out, the mouths of his guests agape. The Renaissance salesmen were crestfallen, convinced their lucrative sale had been squandered. The foundation’s executives recovered their poise quickly, however, eagerly signing a big check. It was going to take more than choking on cigarette smoke and a ruined vanilla cake to keep them from the new fund.

“Any time you hear financial experts talking about how the market went up because of such and such—remember it’s all nonsense,” Brown later would say.

“Our job is to survive,” Simons said. “If we’re wrong, we can always add [positions] later.” Later, some at Renaissance complained the gains would have been larger had Simons not overridden their trading system. “We gave up a lot of extra profit,” a staffer told him. “I’d make the same decision again,” Simons responded.

Medallion was still on fire. The fund, now managing $10 billion, had posted average returns of about 45 percent a year, after fees, since 1988, returns that outpaced those of Warren Buffett and every other investing star. (At that point, Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway had gained 20 percent annually since he took over in 1965.)

[By 2010] The company now employed about 250 staffers and over sixty PhDs, including experts in artificial intelligence, quantum physicists, computational linguists, statisticians, and number theorists, as well as other scientists and mathematicians.

“We’re right 50.75 percent of the time . . . but we’re 100 percent right 50.75 percent of the time,” Mercer told a friend. “You can make billions that way.”

Simons summed up the approach in a 2014 speech in South Korea: “It’s a very big exercise in machine learning, if you want to look at it that way. Studying the past, understanding what happens and how it might impinge, nonrandomly, on the future.”

Mercer was truly self-contained. He once told a colleague that he preferred the company of cats to humans.

Simons couldn’t understand how a scientist could be so dismissive of the threat of global warming, and he disagreed with Mercer’s views. But Simons still liked Mercer. Yes, he was a bit eccentric and frequently uncommunicative, but Mercer had always been pleasant and respectful to Simons.

By the summer of 2019, Renaissance’s Medallion fund had racked up average annual gains, before investor fees, of about 66 percent since 1988, and a return after fees of approximately 39 percent. Despite RIEF’s early stumbles, the firm’s three hedge funds open for outside investors have also outperformed rivals and market indexes. In June 2019, Renaissance managed a combined $65 billion, making it one of the largest hedge-fund firms in the world, and sometimes represented as much as 5 percent of daily stock-market trading volume, not including high-frequency traders.

“I think everything is under control,” Simons said late in 2018. “As long as you keep making money for investors, they’re generally pretty happy.” – Jim Simons